What is HSCT?

According to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society,

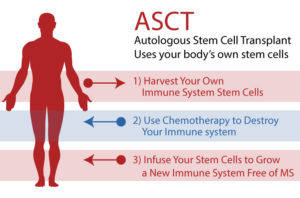

“HSCT (Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation) attempts to “reboot” the immune system, which is responsible for damaging the brain and spinal cord in MS. In HSCT for MS, hematopoietic (blood cell-producing) stem cells, which are derived from a person’s own (“autologous”) bone marrow or blood, are collected and stored, and the rest of the individual’s immune cells are depleted by chemotherapy. Then the stored hematopoietic stem cells are reintroduced to the body. The new stem cells migrate to the bone marrow and over time produce new white blood cells. Eventually they repopulate the body with immune cells. The goal of aHSCT is to reset the immune system and stop the inflammation that contributes to active relapsing MS.”

HSCT was originally developed as a treatment for blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma. The first recorded use of this treatment was as early as 1957. The process has been refined over time, pioneered by Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, here in Seattle, and John Hopkins.

There are two distinct categories of this treatment, allogenic (stem cells from a donor) and autologous (your own stem cells). Allogenic HSCT is more complicated because a patient requires immune suppressive medication to prevent them from rejecting the foreign cells like you would if you had an organ transplant. This is called “graft versus host disease (GVHD)”. Autologous transplants don’t, by nature, have this issue though occasionally one could develop a “pseudo-GVHD”. HSCT for MS uses the autologous process.

Over time, the use of HSCT has branched out into other types of diseases, including some autoimmune issues such as multiple sclerosis. You can read more about this history here.

In 1997 a patient undergoing transplant for chronic myelogenous leukemia also had MS. As a side effect of this treatment, it was discovered that his MS progression and activity had halted. That was the start of research into using this treatment for MS.

Since that first patient there have been many research trials around the world. As I had mentioned in my MS story, I had first bumped into it while working through the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance where I spent a week at UW Medical Center where a patient with MS was part of medical rounds for individuals undergoing HSCT. Canada, the UK, Israel, Italy, Russia, Mexico, and of course the US (among many others) have been working to make this treatment more effective and more safe.

It is still in clinical trials in this country, though many centers will offer this “off trial” to people with MS who meet very strict criteria. Dr. Burt at Northwestern University just published results from a very significant study known as the “MIST Trial” and around the country right now, with one site in the United Kingdom, there is a trial known as “BEAT-MS” that is recruiting participants. As it turns out my neurologist is one of the principal investigators at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center site for this trial.

Myeloablative Vs. Non-Myeloablative

This is one of the big areas of discussion/investigation related to HSCT for MS and other autoimmune diseases. The original treatment developed for cancers involved ablating (removing or destroying) both the peripheral (circulating blood cells) and bone marrow immune systems. The protocol for this, called myeloablative, is considered high intensity, is more toxic, has higher risk of complications and mortality, is a longer process overall, and has a longer, more difficult, recovery time. There are different protocols that fall under this category that are described on a continuum from high intensity to medium intensity. The BEAT MS trial uses a myeloablative protocol known as BEAM which is considered “medium intensity”. High intensity protocols would include irradiation.

Non-myeloablative refers to a protocol that targets the peripheral immune system only. The theory here is that MS, and autoimmune diseases in general, are not a bone marrow generated disease like blood cancers are. Autoimmune diseases, so the current thinking goes, involves some sort of genetic predisposition and an environmental trigger. Your peripheral immune cells become triggered to attack something on your own body cells. In the case of MS that is the myelin sheath on your nerves. Therefore, you don’t need the full myeloablative protocol to solve this problem. The MIST trial with Dr. Burt at Northwestern used the non-myeloablative protocol with similar, positive outcomes to the myeloablative treatment. The non-myeloablative protocol is considered “low intensity”.

“More recently, researchers have conducted trials using less intense chemotherapeutic methods on a wider range of MS patients [20,21]. The rationale for this shift is a growing acceptance of the hypothesis that MS is caused by the interplay of genetics and specific sequential environmental triggers [22]. In this context, eradication of only self-reactive T cells (non-myeloablation) could itself halt MS progression. Full eradication of all of a patient’s hematopoietic cells (myeloablation) is therefore deemed unnecessary and inadvisable given the side effects [23].” Citation.

Depending on the doctor you talk to, which of these protocols is the right one is topic of debate with strong opinions. The predominant research trials currently happening in this country and in Western European countries are almost entirely myeloablative.

Why am I going to Mexico?

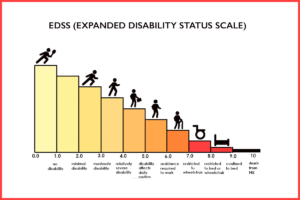

First, all possible sites for doing HSCT in the United States or Europe require you to have the relapsing remitting form of MS, or a “very active” form of progressive MS. You also must have failed several other DMTs before you would be considered. You must be younger than 55 and you have to have an EDSS (Expanded Disability Status Scale) score of greater than 2 and less than 5. The EDSS score is a measurement of disability on a scale from 0 to 10 with 10 being death from MS. I currently have an EDSS of 6-6.5.

The reasoning is that the research shows that the treatment is the most effective on people with RRMS (approx. 90% of RRMS patients have their MS progression halted). They believe that the treatment is so heavy-duty, especially because they are utilizing the myeloablative protocol, that the risk-to-benefit ratio for progressive forms of MS is not worth it in their opinion. FYI, the MIST trial out of Northwestern showed that 66% of people with progressive MS halted their disease. In the opinion of us progressive people (no pun intended) this is phenomenal success compared to the 25% possible benefit of slowing progression with the only drug available for PPMS/SPMS, Ocrevus.

Second, even if I was somehow able to get in to one of these US sites “off trial”, it would not be covered by insurance, and I would have to pay approximately $150,000 out-of-pocket.

Third, “Non-myeloablative HSCT carries less risk of lethal side effects and so the reduced risk-to-benefit ratio of these trials has allowed researchers to extend HSCT treatment to patients with less severe MS.” Citation. This treatment has less risk of death, less severe side effects, and faster recovery time.

Finally, if you look at the diagram above about the EDSS score, I am currently at 6-6.5. I see a very quick path to 9 or 10. A much faster path than I am comfortable with. There are currently no medical options available to me that offer me any hope of changing that trajectory. HSCT isn’t a guarantee, but it has very good odds. Further progression of my MS without HSCT is a certainty.

There are two facilities that have been doing this non-myeloablative protocol with phenomenal success for close to 20 years – Moscow, Russia and Puebla, Mexico. For the most part, their protocols are identical with one important difference that swung me towards Mexico, in addition to less complicated travel.

In Mexico, they divide the chemotherapy days into two, 2-day sessions with about a week between. This allows for less stress on your kidneys which is important for me because I have had multiple kidney infections in the past and feel it is important to protect them. Russia clumps the chemotherapy part of the process into four consecutive days.

Both sites are highly reputable with very respected physicians running their programs. They are well known to providers in this country, and it is not uncommon for neurologists to give their blessing to progressive patients to take advantage of this opportunity – “I would do it if I were you”.

What is the Protocol?

I will do a very basic outline here and may come back and flesh it out later.

I arrive and do several days of testing to make sure I am safe for the treatment. This involves cardiac function, lung function, MRI tests to look for cancers, tons of blood tests, etc.

The next step is two days of cyclophosphamide chemotherapy to begin to obliterate my existing immune cells.

I then have seven days of injections to stimulate my bone marrow to overproduce stem cells.

Next is the insertion of a central line port to harvest stem cells that same day.

I then have another two days of cyclophosphamide chemotherapy.

The next day is what is known as my “stem cell birthday”. My stem cells are re-transplanted into my system to begin rebuilding my peripheral immune system. It is important to note here that the stem cells are the critical part of this treatment. The chemotherapy and the obliteration of the existing immune system is the key part of the process. The reintroduction of stem cells is important to help rebuild the immune system quickly for safety.

For the next seven or so days I am in what is known as a “neutropenic phase”. We will stay in our apartment in complete isolation. My apartment will be disinfected daily and I will have blood labs drawn regularly to monitor my immune system recovery until I reach a point where I am safe for the next step.

Around eight days after my stem cell transplant I will be given a large dose of Rituxan/rituximab and the next day I will be put on an airplane home.

Recovery

Once I return home, the recovery and healing begin. This part is hard to predict. Many people describe the first year as a roller coaster. I expect the first month that I am home I will pretty much feel like crap and sleep a lot. I am also extremely immunosuppressed, so I must be incredibly careful of exposure to infectious invaders.

I have a hematologist/oncologist on my care team here stateside. He did a bunch of preliminary blood work and assessment of my health status before I left, and he will monitor my recovery when I return. I will have regular blood labs to see how my immune system is recovering and to make sure I am not acquiring any dangerous infectious issues. The expectation is that I will have full immune system recovery by six months, though it could be sooner.

In my research I have learned to expect that I will have periods of time where my existing MS symptoms roar up quite loud and then quiet back down. For some people that lasts a couple of days, for some a couple of weeks, and for some months.

Spasticity is one of my most challenging symptoms currently. It affects my walking. It affects my arm and hand function. It causes me pain. It is not uncommon for people to experience debilitating spasticity around the eight-month mark whether they had it before or not. For some this spasticity lasts for a year, for some less time and for some it can become permanent. This is my biggest fear during recovery.

Whether my MS has been halted and whether I have any symptomatic improvement will take a long time to know. There is no objective measure to determine if my MS has been halted. There is no blood test. There is no MRI scan to tell if I am having less lesions. Remember, I have not had new lesions since I was first diagnosed in 2007. It is only my own experience of my body that will help me know if this whole massive experiment worked.

The clinic collects quarterly surveys about patient experiences to track success or to know if someone is what is called a “nonresponder”. Many people experience distinct improvements that help them know it was beneficial. The most common symptom improvements are decrease or disappearance of fatigue, decreased or disappearance in bladder symptoms, and decrease or disappearance in cognitive issues. There are people who also see improvements in their mobility challenges, and I only hope that I will be one of them.

It is not uncommon for people to continue to see improvements over the next two or even four years after transplant. This adventure is a long game. If it is successful I will be able to maintain my current quality of life and potentially recover some of what I’ve lost.